Hops Are Hopping

March 11, 2016

Northern Michigan’s Latest Ag Revolution Is Changing the Landscape

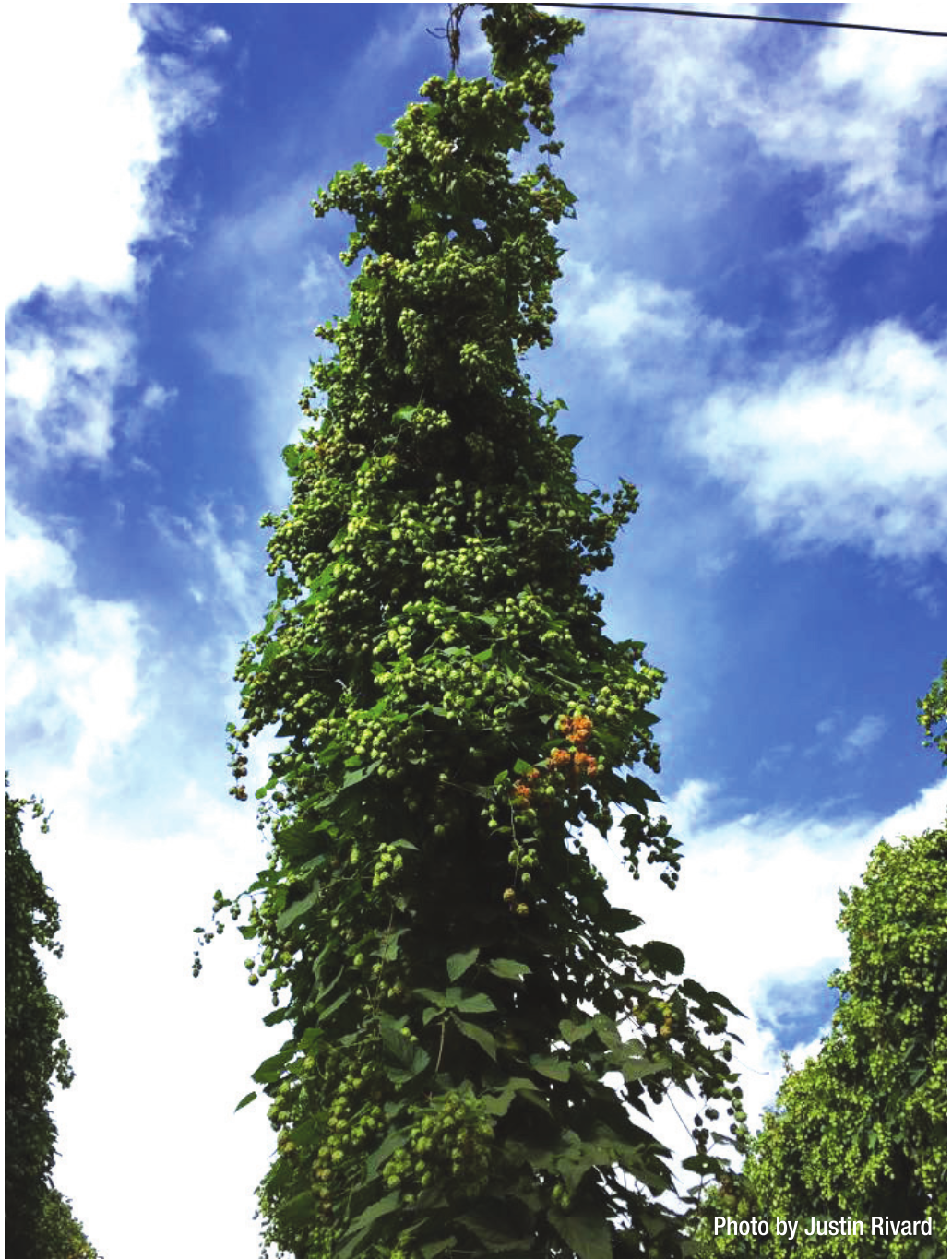

Hop

lots look a lot like vineyards, only taller — like vineyards on stilts —

and the strange sights are becoming more common. While only a decade

ago there were none, today hops farms are quickly becoming a staple of

northern Michigan’s economy.

POPPING

UP HERE AND THERE The area’s first hop farm was planted at the tip of

the Old Mission Peninsula, followed soon after by plots near Empire and

Omena. The hop-tenders in Omena came to the business by chance.

“We bought 10 acres about 10 years ago to camp on and things got out of hand,” said Brian Tennis, owner of New Mission Organics and creator of the Michigan Hop Alliance, who quit his corporate job in February because hops have taken over his life. “Now we’ve got 30 acres in hops and we’re looking to buy more property to expand.”

When Tennis and his wife, Amy, began, they had no idea what they were getting into. They’d never even farmed before. They bought a small organic farm and tried to work some of the cherry trees.

“Those cherries were on the property when we bought it and we had never farmed before, so we were just like, ‘How hard can it be?’ So we started with a couple acres of organic cherries and that was just a disaster,” Tennis said. “We didn’t have a tractor, we didn’t have a sprayer. We didn’t even have a barn or electricity. So we were basically camping and trying to take care of these trees. It just wasn’t working.”

Back then, they never even dreamed of hops. “We had no idea what a hop was 10 years ago,” Tennis said. “We loved beer. Even when we were broke, we always drank really good beer.”

He said he used to make beer in small batches on his stovetop.

“Hops back then — it was just whatever came in the kit,” he said.

A

CAMPAIGN TO RECRUIT FARMERS A seminar changed everything. The explosion

in craft beer that began in the late 1990s slowly caused demand for

hops to spike. Those high prices started to worry brewers.

Rob Sirrine, an Michigan State University extension educator in Leelanau County, recalls a meeting he helped organize in late 2007 to stir interest in hop farming.

“There was a real, or perceived, hops shortage; we had had brewers call us, interested in having hops grown locally,” Sirrine said. “They were definitely concerned about the future market security of hops and if there would be enough to go around.”

The impact craft beer had on the hops price was striking. While they sold for $1.90 per pound in the early 1990s, in 2007, hops cost as much as $25 per pound, Sirrine said.

“It’s one of those markets that’s kind of been boom-bust-boom-bust over time, but that was before this craft beer explosion,” he said.

That hops summit brought farmers, a hops grower from New York, an expert from Colorado, and brewers and brewers to the Hagerty Center.

Tennis attended and said a small northern Michigan agriculture revolution started at that meeting.

“That’s really where it all started. I mean, there was a couple of guys up here in northern Michigan, including myself, who went out that spring and planted the first acreage,” Tennis said. “Before we started growing hops, we had never grown anything commercially, so we just went for it.”

HOPS ARE HOPPING Today, the region’s hops industry is booming and it’s got plenty of room to grow.

“Right now, Michigan is the fourth largest hop-producing region in the United States and we’ve only been doing it for eight years,” Tennis said. “And we’re also in the top 10 regions in the world now, after this year, with all the acreage that’s going in.”

Tennis said it makes sense for Michigan to be a big player. Hops, like cherries and wine grapes, grow best around the 45th parallel, and Michigan has already carved out a reputation as a great beer producer.

“We’ve got world-class breweries, so now we have to focus on providing them with world-class hops,” Tennis said. “I think we’re a lot closer to providing that world-class product than we were just a couple of years ago.” The Michigan Hops Alliance, a co-op of roughly a dozen small growers, represents about a quarter of the hops grown in northern Lower Michigan, Tennis estimates.

What’s currently grown in northern Michigan can barely keep up with demand.

Tennis said he doesn’t just sell to northern Michigan brewers. He’s got customers all over the country; he’s got customers in Europe. In early March, a truck from Bang Brewing, a small brewery in St. Paul, Minn., came to Traverse City to pick up 500 pounds of whole cone hops.

“We keep buying 10 acres when we can afford it,” Tennis said, “but now that we’ve got some partners, we’re really going to be looking at really dramatically increasing that acreage.”

Even as demand seems to only be on the rise, Tennis said the industry is rapidly changing so that small-scale hops growers cannot make it on their own.

“The

business model has changed so drastically in the past 24 months,” he

said. “A hundred acres is probably a good starting point if you’re

serious about growing hops here in Michigan, because you need that

economy of scale to get your price down.”

A MORE SECURE WAY TO FARM MI Local Investment President Jason Warren, owner if MI Local Hops, will be come the area’s largest hops grower this summer. MI Local has 200 acres of hops installed and ready to produce this year, Warren said. They plan to produce at least 400 acres or more at the former site of High Pointe Golf Course in Williamsburg.

Warren has even bigger plans, though.

A processing plant where hops can be stored, dried, processed and pelletized is under construction. Warren hopes to open a wedding venue to take advantage of the beauty of the rolling hills and distant bay views, and he would also like to launch a tasting room and restaurant exclusively featuring beer from breweries made with hops from his farm.

Warren comes from a five-generation Old Mission Peninsula cherry farm family, but he didn’t want to be a farmer when he grew up. When he went to college, he wanted to get as far from the orchard as he could. He became an accountant and, although he worked with food processors and farms, he preferred crunching numbers to shaking cherry trees.

“Actually, I purposely went to college and got an accounting degree and a CPA certification to not work on a farm,” Warren said.

He said the life of a cherry farmer involves too much risk: one late frost can destroy an entire season’s harvest.

The more Warren learned about hops, the more he believed he’d found a hardy crop that would be immune to the fluctuations of northern Michigan’s unpredictable climate. Hops can handle early springs and late frosts. Direct hits from hail or severe wind are about the only weather events that can destroy the plants.

THE DOWNY MILDEW CONCERN Still, the biggest worry for growers may not be whether craft beer stays popular and the price of hops remains strong. What worries Warren is what wiped out Michigan’s hops industry in the 1920s: downy mildew, a crop disease that, once established at a farm, could hop from hop lot to hop lot.

“Our biggest challenge up here is the downy mildew,” Warren said. “If you know what you’re doing and know how to manage it, it should be totally manageable.”

Crops need to be sprayed at particular times and watered in a precise way, at the base rather than over the plants. The trouble is, one hops farmer can do everything right and still see crops damaged by mildew if mildew breaks out at a neighbor’s farm, Warren said.

“I’ve been told that the spores for that can travel up to 10 miles, and that’s one of the reasons, to be honest with you, why we chose to put our operation at this location,” Warren said.

MI Local Hops is located several miles into the mainland of the lower peninsula, putting a good buffer between it and the farms on the Old Mission and Leelanau peninsulas.

Sirrine said growers need to stay on top of it to protect their hops from downy mildew, but with vigilance, they should be okay.

He said the bigger problem is that growers today are getting rhizomes that are already infected with the mildew.

Tennis said his co-op is working on that problem at a Leelanau County greenhouse, where they are trying to grow clean rhizomes to sell to growers. Those plants will be more expensive, but they should be hardier and live much longer than non-sterile rhizomes.

CONFERENCE THIS WEEK Sirrine’s work to bolster the industry continues. He’s helped put together the Great Lakes Hop and Barley Conference Mar. 16 and 17 at the Grand Traverse Resort, an event geared toward people in the industry or anyone interested in growing hops or making beer.

While the region’s hop production has exploded in recent years, Sirrine believes it can continue to grow because the craft beer market continues to grow. Craft beer is projected to comprise 20 percent of the beer market in 2020; it made up just 11 percent in 2014. Demand for hops will also grow because of the way craft beer is made. More hops go into a bottle of, say, Short’s Soft Parade than into a bottle of Budweiser. And specialty hops remain in high demand. An online review found that organic hops can still go for $25 per pound.

Hops farmers don’t expect high prices to last forever and they expect market volatility will return someday. Just as Warren wants to open a tasting room and restaurant in 2017 or 2018, Tennis also hopes to liberate his business from the per-pound price of hops.

Tennis and his partners plan to open a farm-to-tap brewery, perhaps next year. The brewery would bottle and can its own brand of beer and feature a tap room, Tennis said.

“We’re really looking at doing our own brewery to insulate us a little bit between the fluctuations and costs,” Tennis said.

Tennis finds himself far from where he was a decade ago, when he moved from Grand Rapids to Suttons Bay, planning to work his IT job at Zeeland-based Herman Miller remotely. Quitting the job this February was difficult, he said, because it meant giving up the security of a corporate safety net. Tennis loves his new job, but it comes with a lot of work.

“It’s to the point now where we’re just so busy,” he said. “A lot of people think they’re going to get rich by jumping into the, quote unquote, hop game, and you know, they get into it and they realize it’s a lot of work. It’s a lot of capital. And prices do go down.”

Trending

Springtime Jazz with NMC

Award-winning vibraphonist Jim Cooper has been playing the vibraphone for over 45 years and has performed with jazz artist... Read More >>

Dark Skies and Bright Stars

You may know Emmet County is home to Headlands International Dark Sky Park, where uninterrupted Lake Michigan shoreline is... Read More >>

Community Impact Market

No need to drive through the orange barrels this weekend: Many of your favorite businesses from Traverse City’s majo... Read More >>