Recapturing Our Heritage, One Apple at a Time

Things our ancestors valued are finding favor: chairs from the late 1800s. Dressers from the time of the Revolutionary War. And don’t forget Aunt Lucy.

That’s not a relative, but an antique nevertheless. So-called antique apples date back 50, 100, 150 years ago. Favored varieties such as Macintosh, Paula Red, Granny Smith, and especially Red Delicious took over shelf space, while Sunset, Grimes Golden, Hawkeye Greening and, yes, Aunt Lucy, became all but unknown.

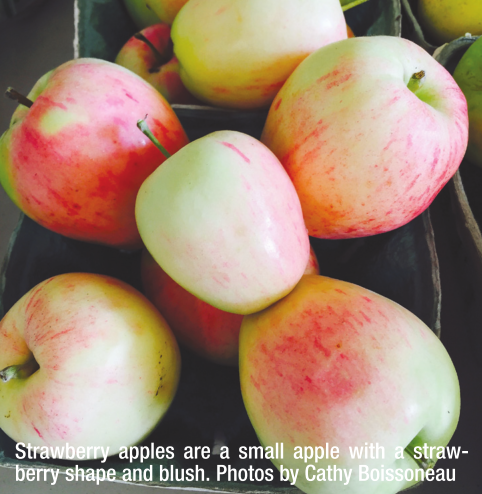

Also known as heritage or heirloom apples, they come in all shapes, sizes, and colors. They may be large or tiny, oblong or oval, with red, green, brown, even striped exteriors.

In part, that is why they became antiques, as they were less easily marketable than their cousins. Today, however, aficionados are working to preserve and in many cases rediscover these unique strains.

Among them are John and Phyllis Kilcherman of Northport. Their Christmas Cove Farm is home to more common types like Gala and Ginger Gold, as well as Duchess, Wolf River, Winter Banana, and Thomas Jefferson’s favorite, Spitzenburg.

“I started planting them to find their value compared to the more commercial apples,” said John Kilcherman. “I’d plant one of this, two of that, to see what they were like.”

While he was planting, Phyllis was trying out the various types to see how they could best be used. Some turned out to be great for pies, others for applesauce. Still others were delicious fresh from the orchard.

Today, with over 200 varieties, the Kilchermans operate the largest antique apple orchard in northern Michigan.

While their stock may boast the greatest variety, the Kilchermans aren’t alone in their enthusiasm. John King of King Orchards in Central Lake harvests several types of antique apples: Cox’s Orange Pippin, Newtown Pippin, Cortland, Lodi.

Most of what he harvests he uses isn’t used for eating or baking. “We have a real interest in cider varieties,” he said.

King does save some of the heirloom varieties for his farm market and events like the Charlevoix Apple Festival. “We take some Snows and others to that,” he said. *** Apples were a main food source for the pioneers. They would plant apple trees where they homesteaded. Various types ripened at different times, from midsummer to late fall, with the latest-ripening varieties remaining edible for months after harvest.

As refrigeration became common and the grocery industry utilized transportation to bring in and ship foodstuffs to and from distant places, the need for long-lasting fruits lessened. Instead, appearance and uniformity became crucial, and the Red Delicious and a few other varieties came to dominate the market.

As the years flew by, many former homesteads and farms were surrendered to the vagaries of nature. A number of them along the lakeshore are now in the National Park. Though untended for many years, abandoned orchards around Empire, Port Oneida, and the Manitou Islands still produce fruit.

One of the largest is the remains of a commercial orchard on North Manitou Island, started in the late 1800s by Frederic Beuham. In 1893, he contracted with orchardist William Stark, one of the brothers of Stark Brothers Nursery. Although no buildings remain, the 160 acres still contain as many as 700-1000 living apple trees.

Staff from the National Park Service and the Leelanau Conservation District, along with volunteers, are trying to save and reproduce them before they are gone forever.

Tom Adams, Natural Resource Specialist at the Conservation District, said the attempts have been mostly successful. “We’ve grafted 200 trees, and had 190 take,” he said. *** While many of the antique varieties are exquisite when picked and eaten, others reveal their true character when cooked. Duchess, for example, is favored for pie and applesauce.

Another popular use is in cider making.

The Kilchermans combine many different apples for their cider, as does King Orchards.

At Royal Farms in Atwood, Sara McGuire said they grow their own apples for use in their hard cider. “We use a handful of varieties: Kingston Black, Wolf River, Winesap, Brown Snout,” she said.

McGuire said cider apples often have a different flavor profile than apples for eating or cooking. “What goes into a lot of cider is bitter or sour. It’s different than what is typically an eating apple.”

Another reason some are more popular when made into juice or cooked is that their appearance might not be as appealing. “Some skin is tough,” McGuire admitted.

Still, the fact these old apples are new to most people helps keep them interested. “People are always curious,” she said.

That’s true in spades at Kilcherman’s. Visitors from all over make the drive to the farm. They frequently host guests from downstate, other states, even as far away as China. “I always ask them where they’re from,” said John Kilcherman.

“We get people from all different countries,” said Phyllis. “For us, that’s the fun part.”

View On Our Website