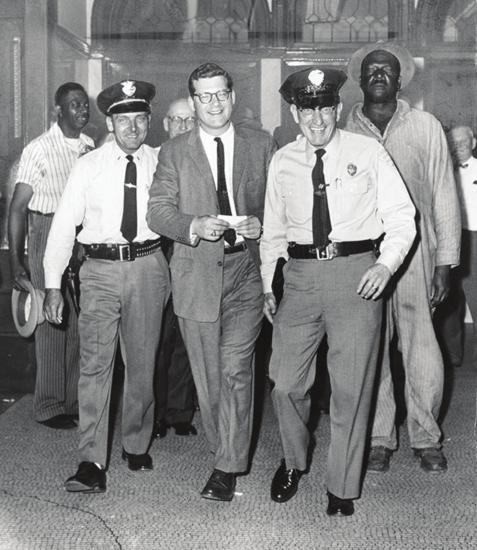

A Black And White Snapshot Of Tim Green

My old law partner Merritt W. Green II – Tim – died last month. He was born with a gift of laughter and a sense of social justice.

The black and white snapshot from 1960 shown here – the old courthouse, the terrazzo floor, the arched windows, the white cops, the large black man in work clothes, Tim – shows exactly what he was. It’s 1960; the Civil Rights Act hasn’t been passed yet. Tim’s being taken to jail; the cops are laughing at something he just said; his black client looks like he wants to protect Tim.

I have a summer vacation memory from a year earlier, in 1959, when I was sightseeing in Washington, DC. It’s a stifling day; I"˜m standing outside the U.S. Capitol pitching pennies in the fountain for little kids to retrieve. Three white teenage hooligans run up, grab the little kids by the heels and drag them up the stone stairway. I can almost feel it as their heads bang the steps. I am transfixed by the terror in the eyes of those little black faces staring up at me as they’re dragged feet-first. It’s my first time seeing racial violence. I’m speechless, and then my friend’s mom says, "We can’t watch this," and turns us away.

It didn’t sink in until years later that the white hooligans were dragging the little kids into the Capitol, apparently to report them for playing in the fountain. They weren’t hiding their violence; they were doing what passed for morality in the United States in 1959.

Back to the snapshot. In 1960 in Toledo, Tim Green represented black longshoremen, Local1317-A. But the operators of the Toledo Maritime Terminals (TMT) didn’t like it, and went into a bigoted local court to get an injunction to stop the men from picketing. Tim told the men they were right and the TMT was wrong, and that he would back them if they challenged the local judge’s attempt to decide a federal union rights issue.

There was a court hearing and principled, emphatic words were exchanged. The judge – with obvious relish – threw Tim in the clink. As Tim was led away, his client hovered, upset. Tim told the cops his view of the situation and they laughed with him, as everyone always laughed with Timmy.

About two years later, after refusing publicly to apologize to the judge, Tim was exonerated by the United States Supreme Court in the landmark case, In Re Green.

The icing on the story came afterward. A local newspaper reported that the local judge, who had bristled at Tim’s "brazen and bold" advice to the strikers, was bitten by a dog. Tim sent the owner a 25-pound bag of dog food.

If you mourned the figurative passing of heroic Atticus Finch in Harper Lee’s second novel, you should mourn again. For Tim Green was the real Atticus, and there will be no rewrite of Tim Green. He was unique, unalterable.

Tim was a strong, beautiful specimen of a man with a ringing laugh. He was the captain of the University of Michigan football team; he played tight end before they used face-guards; he wouldn’t stay at a hotel that turned away a black teammate. He was a groomsman in the wedding of Roger Wilkins, nephew of the NAACP director, at a time when it rated a news story for a white to be in a black wedding. When Tim represented African Americans trying to register to vote in the Deep South – I capitalize the place as if it were another country because it was in those days – he took a telescope for star watching because he’d heard the night sky was clearer in Alabama. Tim stargazed in a war zone.

He flew a twin Beech Baron; his wife, Patti ,was an investigative journalist who flew her own Cessna. When they crashed in the mountains of Mexico, he guarded the plane while she hitchhiked in search of a car. He represented seven of the Edmund Fitzgerald families. He won a $7.5 million verdict against a railroad. He was the godfather of his favorite bartender’s grandchild in Zihuatanejo, Mexico. He wrote long prose with the best of them and knew hundreds of jazz recordings by heart. He co-founded Advocates for Basic Legal Equality (ABLE). He knew bars well and wherever he sat it seemed the room tilted toward him, and every person wound up at his elbow, telling Tim a story.

Tim lasted 85 years. But playing tight end catches up with you. We had dinner and a beer shortly before the end, and he cursed the pain as he laughed over memories. He didn’t want to quit, but he’d decided to take a long time-out. One of his favorite books stuck out on the bookshelf:

"To be a man is, precisely, to be responsible. It is to feel shame at the sight of what seems to be unmerited misery. It is to take pride in a victory won by one's comrades. It is to feel, when setting one's stone, that one is contributing to the building of the world." (Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Wind, Sand and Stars)

To feel the shame of another’s plight, to be entitled to avert his gaze, but instead to confront the shameful thing and demand justice– that was Tim. That’s the black and white of it.

Grant Parsons is a Traverse City native and a trial attorney with a keen interest in local government.

View On Our Website