A Soldier‘s Story

March 14, 2007

Jonathan Reed talks about greedy interpreters,a fallen friend, and tight-lipped Sunnis

Editor’s Note: To mark the fourth anniversary of the war with Iraq, Northern Express interviewed Jonathan Reed, a Munson Medical Center nurse who served in Iraq until last July.

Jonathan Reed looks like a soldier. Clean-cut, athletic, and handsome. He grew up in Traverse City, the son of a Vietnam veteran. Reed signed up for the military reserve right out of high school, in part, because his father taught him that it was important to serve the country. Reed also wanted to attend Northwestern Michigan College, and needed the military benefits to help pay tuition.

Reed was on active duty with the Army reserves for four years, training one weekend a month. Then he went on inactive status in 2002, a year before the Iraq War began. He didn’t worry. The high school recruiter

told him that inactive reserves were rarely called upon.

Suddenly in late May of 2005, Reed received a letter in the mail. He was ordered to report to a base in South Carolina in six weeks. Reed, then 25, was divorced, and the father of two boys, ages two and four. He was five months into his first nursing job at Munson Medical Center. “I was shocked. There was just a letter that came to my mom’s house. I didn’t even have to sign for it.”

Reed and 19 other infantry soldiers—all with security clearances—learned that they would serve as guards for small military intelligence teams in Iraq. Reed made several phone calls to remind officials that he was a nurse and had submitted paperwork for a medical assignment. He was told it was too late to make changes. “I felt shafted. I felt my skills would be pretty much wasted, especially with the shortage of medical personnel.”

With his fate fixed, Reed shipped out to Iraq on September 28, three days after his 26th birthday.

Here’s an interview:

NE: Were you worried about getting your job back at Munson?

REED: No, Munson was great. They held my job and my seniority and retirement accrued just like I was there. They were even going to pay the difference of my military pay, but I ended up making more.

NE: What did you do once you arrived?

REED: We spent a month in Baghdad, sitting on base while our team got ready. We weren’t doing anything, and that gave me way too much time to think about not being home. They wouldn’t let us go out on missions to get some experience, so we just sat around.

In mid November, we finally flew up north. Our five-person unit tagged along with the patrols of the 101st Airborne Division. We had our own truck and our own set up, but we were not allowed to go out alone. It was too dangerous.

Our military intelligence leaders would try to stop at a village and talk to the muchtars, the village leaders, and see if they could get information from them. My job was to either drive the Humvee or man the turret gun.

NE: Did your military intelligence leaders speak Arabic?

REED: No, they had an interpreter. Most of the time we stayed in the trucks. Whenever we stopped, the people would get out, and the gunner and driver would provide security. The 101st soldiers would go with them.

NE: Was it scary?

REED: Yeah. The area we were in was pretty much Sunni, and the people had strong support for the insurgency. The locals wouldn’t help us very much at all. A couple of sources would tell us things, but they weren’t reliable—they were in it for the money. It was frustrating because we weren’t getting any help from the Iraqis. The soldiers of the 101st said, “Screw them if they’re not going to help us help them. Why are we wasting our time?”

NE: Was there much bombing there?

REED: Around Christmas time, a woman named Myla Maravillosa, she was around 25, went on patrol. Her truck was hit with a rocket grenade; the shrapnel penetrated the rear wheel well and killed her.

NE: Did that affect you?

REED: Yes it did. I didn’t know her that well, but I did know that she was an only child who grew up in the Philippines and moved to Hawaii when she was 16. She was very religious and always went to both the Catholic and Protestant services. I remember that evening, on Christmas Eve, I and another team member packed up her belongings to send to her mom. That’s when it hit me the most. Trying to inventory her things seemed kind of surreal.

NE: Did your truck ever get hit?

REED: Yes, we were just coming back from a patrol, and I was up in the turret, facing the other direction, my back to the shoulder of the road, and it exploded on our truck. It was a big boom. It flattened our tires and shrapnel hit my machine gun. It’s funny. The worst part is waiting for it to happen, and then when no one gets hurt, you just go on.

Another time, we had an Iraqi who accidentally got shot by one of our gunners. A soldier had fired some warning shots, and the bullets bounced up off the dirt and hit the Iraqi’s legs—he was on a motorcycle. They tore up his arteries. That was the first chance I got do something medical. I helped the medic put tourniquets on his leg, and got the IV started with some morphine. There was another guy I helped with glass in his head.

The interesting thing was that most of the soldiers thought of it as a big inconvenience. They felt like now we had to stop our mission, go back and evacuate him, and he

was probably an insurgent anyway. Their attitude bothered me at first, but I could understand it.

The soldiers were good with the kids, though. They gave the kids stuff even though they were annoying. They’d steal stuff right off you, if you’d let them. People kept that humanity, but toward the Iraqis there was callousness because most of the people wouldn’t help us. When Mila got killed right in the downtown, nobody saw anything, and you know that they did. That was frustrating.

NE: Did you feel like you might be next?

REED: I felt that the odds were in my favor, but you live in a kind of tense state anyway. There was a sniper in the city, and he had shot several soldiers. So when I was in the turret, I had to sit low so my helmet didn’t stick up. You felt as if you were just waiting for someone to attack you. And even fighting back, you were limited by the rules of engagement before firing. That was frustrating because sometimes you have to make a split-second decision.

NE: What are rules of engagement?

REED: There were specific rules of escalation. Deadly force was the last step. If a vehicle was approaching, you first used hand signals, then a warning shot to disable the vehicle, and then deadly force was the last step. But if things happened too quickly, you wouldn’t have time for that progression. You felt that if you didn’t fire, you could get blown up and die. But if you did fire and you’re wrong, you’re punished for not following the rules. The system didn’t give you the means to make the right decision.

NE: What were your living conditions like?

REED: We slept in small trailers, large metal shipping containers that had been converted into sleeping quarters. We had a couple of windows, covered with sand bags. Each one had a heating and air conditioning unit, two sets of bunk beds, four to six soldiers sharing the trailer that was eight feet wide and 14 feet long.

NE: Where did you go next?

REED: In early March, they sent me to Kirkuk, an hour away from the base that I had been on. The unit I was on did reconnaissance work, but I stayed on base and worked in the aid station. But since I hadn’t been medically trained under the Army rules, I wasn’t allowed to do anything. As it turned out, I had a medical condition that got worse from riding around in the Humvee. I had my first surgery there, and that didn’t fix it, so I flew to Qatar, on the other side of the Persian Gulf. It was an Air Force Base, and I spent 10 days there. And that was interesting.

NE: How so?

REED: Just seeing the difference between the Air Force and the Army.

While I was in Qatar, I learned that most of the Air Force people only do four-month tours, while the Army serves for a year. It felt like our branch of the service wasn’t looking after us as well.

NE: Where did you finally end up?

REED: In Balad, about 50 miles north of Baghdad. I worked in the operations center, mostly classified stuff. We’d look up intelligence reports and in the morning, we’d give a briefing to our commanders.

NE: Sounds interesting.

REED: It was. That was the best base I was on. We had a swimming pool, only two of us sharing a trailer; that was the best living I had.

NE: A lot of people say the media rarely captures the reality of what’s going on. What is the reality?

REED: It’s hard to get a picture because there’s so much variation, depending on where you are. In the northern Kurdish areas, they rarely get attacked. Other places get attacked all the time, where there is a mix of Sunni and Shiite.

NE: Did you ever get a chance to talk to the Iraqis?

REED: Not much. We’d talk to them a little bit if someone came into the office, but for the most part, we were on the sidelines. I had ambitions of learning Arabic, but it died when we got to the Sunni area and they didn’t want to talk to us anyway.

NE: Did your opinion about the Iraq War change as you spent time there?

REED: Early on, I was leery of the intelligence that was used to justify the war. I think at the beginning a lot of Americans were duped—the administration tried to make it look like there was an imminent threat. By the time I went, people had realized that the intelligence had been very sketchy.

So I didn’t want to go, but I had signed a contract and I had to go. While I was there, I came to feel more that the war was not going anywhere, but we needed to stay so we could fix it. It seemed to me then and largely still does that much of their struggle is rooted in the struggle for power and religious beliefs. I don’t know if they’re going to overcome their differences and work together.

NE: Did you ever share your opinions with your fellow soldiers?

REED: Not so much. There are liberals in the military, but it’s conservative- dominated. There is talk, but not a lot of really open dialogue. Especially not on active duty. Dissenting can be seen as something more serious.

NE: I just read they are trying to work out an agreement on sharing oil revenues.

REED: That sounded encouraging. Oil is concentrated in certain areas, and the Sunnis are all worked up that they won’t get their share. An oil agreement will help. The other part is the power issue. The Shiites have much larger numbers than the Sunnis, but the Sunnis have been in control for almost 30 years. They’re not happy about being forced to accept this little piece of power.

NE: How do they resolve this?

REED: I don’t know and I’m not sure anyone does, except to let them fight it out. What other option is there?

NE: What about the idea of immediate troop withdrawal?

REED: I don’t think that’s a good decision because we have to give them a chance to take control for themselves, even if it doesn’t last. I agree with Senator Levin that there has to be a time line for a transition plan. We have to ask them to achieve goals in a certain amount of time, and when that time comes, we’ll withdraw.

If that happened, I think the Saudis and Iranians, who have stayed on the sidelines, would take an active role to maintain stability. I don’t think it would just spiral, although there will be a fair amount of loss of life. I think the country would separate along ethnic lines and some kind of stability would take root.

NE: Does it hurt soldier morale to question this war?

REED: I don’t think so. Soldiers have to follow orders of their commander. Our soldiers are doing a great job, but their leaders are not giving them the right direction. Now retired generals are coming out and saying the war was wrong from the beginning, that the administration ignored what they said about the troop levels.

NE: How is the morale?

REED: On different levels, it is good. The American taxpayers are paying a lot of money to keep the soldiers happy. Even on the smaller bases, we had Internet access and phones. On the larger base I was at, we had an Olympic-size pool that was once used by Saddam or his people. Life is pretty good when you get to swim every morning.

On the smaller base, we didn’t have the amenities. It was about the size of the Civic Center. There was no TV, and we were mortared all the time.

At that base, we had a shortage of sandbags to put around our trailers, and one of the trailers had no sandbags at all. We had the bags and we had sand, but they wouldn’t let us fill them because they wanted to hire local Iraqis to do it. But it was such a process to bring them in and guard them, so we had no sandbags.

We tried two different times to do it ourselves, and twice we were told to stop. So we lived in a trailer with no sandbags. That seemed pretty idiotic to tell soldiers they can’t protect themselves. I wrote to my dad that if I got killed, please get somebody fired.

NE: What’s your impression of Halliburton?

REED: It is pretty much running the country from what I can see. On the larger bases, everything is done by KBR (Halliburton) – the laundry, the chow halls, housing and recreation, the gyms, the pools, pretty much everything. Americans are the managers, and the laborers are all foreign-- Filipino and Asians and Indians.

NE: Any resentment about contractor pay?

REED: I know that the pay of interpreters was an issue. There weren’t enough interpreters to go around, and that limited our intelligence team. Most of the interpreters work with the Titan Translator Service and earn $90,000 a year.

Our first interpreter was a real nice guy from Detroit. He did a great job, he really cared about helping us. Then we got another one from Connecticut. He was an Egyptian and he’d routinely refuse to go on a mission if he thought it was too dangerous. That really made some people mad, and they tried to get him fired or moved to another spot. He did get moved, which is what he wanted. And he was getting paid the whole time.

Then we had these locals; they would go out, a couple of them got killed, and they were making $1,000 a month, which was really good money for them. They just really cared. One guy was 22 or 23, he wanted to help the country, really wanted to move here someday. It was frustrating when you met Americans who were just there to make a buck.

NE: What was your high point in Iraq?

REED: After I had my surgery in one of the larger hospitals, there was a bombing at a market, and they evacuated about 30 people to the hospital. So I spent the night treating a lot of burns and shrapnel wounds. That was the most useful I felt the whole time, and it reinforced my frustration that I wasn’t being used as a nurse. I could have been doing that everyday and my time would have been well spent.

NE: Any problems with post traumatic stress disorder?

REED: I don’t think so--the Army did a good job of screening us for that when we got out.But I have some stress to work through.

About a month after I got there, I was in the turret of a Humvee at night, and the driver’s goggles malfunctioned. I got out of my turret to help him out, others were trying to help him out, and none of us saw the barrier until the moment we hit it. (The Iraqi police put up the concrete barriers as checkpoints.) I was the only one without a seatbelt, and we hit the barrier at 30 mph. I got a cut on my forehead from the goggle and whiplash, and after that I got real edgy when we had to drive at night. Real nervous. It still really bothers me when I can’t see when I’m driving, when the window fogs up, any time I can’t see.

NE; Did your experience in Iraq politicize you?

REED: Yes, because I’ve felt the government hasn’t been looking out for the soldiers. I talk to people about it a lot. Some of the more conservative people I work with were taken aback when what I said didn’t match up with what they thought. I just joined Veterans for Peace. I’m looking to get involved in the activities that are going on around the fourth anniversary, talk to people about it.

Trending

Pride Month Celebrations in Northern Michigan

As June rolls around, northern Michigan communities come alive with vibrant celebrations for Pride Month. This year, the LGB… Read More >>

Walking a Mile in Someone Else’s (Famous) Shoes

By now, there are few who don’t know of social studies teacher Matt Hamilton, or his labor of love, the East Jordan Sh… Read More >>

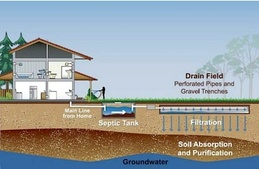

Think Septic Before You Sell

Thinking of putting your house on the market next year? Despite being the Great Lakes State, Michigan is the only state in t… Read More >>