Lucky Larry Lampton, 75 years after D-Day

Decorated Traverse City veteran was one of 18 of his 71-man crew to survive Omaha Beach

By Al Parker | June 1, 2019

Leonard “Larry” Lampton isn’t comfortable being called a hero.

“We were just doing our job,” said the soft-spoken Traverse City man, referring to his role in the largest invasion of World War II, on June 6, 1944, D-Day.

Modesty aside, Lampton’s memories of that historic day, 75 years ago, burn bright and his story could easily be part of a Hollywood adventure tale.

Born in Louisville, Kentucky, Lampton and his family moved to Detroit, where he attended Southeastern High School. With the U.S. deeply involved in World War II, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy in January 1943.

“It was what you did then,” said Lampton, who will turn 95 in June. “Everybody was patriotic and wanted to do our part.”

After basic training, he was trained to be a diesel mechanic. “Little did I know that the only diesels were on landing crafts and submarines,” Lampton said with a laugh. “But at least I didn’t get submarines.”

In 1944, he was chosen to be part of an elite “special support group,” and underwent rifle training, electrical, welding, and other skills. “There were 1,500 of us, and it was all hush-hush,” he said. “We didn’t know why we were doing this.”

He soon found himself with about 20,000 U.S. troops aboard the Queen Elizabeth II heading to Europe. Taking a zig-zag route to avoid German submarines, the QEII docked in Scotland, where they were re-assigned as crews.

After a while, it was soon apparent that Lampton and the others would be the “spearhead” of the invasion of Europe. “We knew then that we were going for that,” he said.

Seventy-five years later, the D-Day invasion may only be a paragraph in a history book to some generations. But in 1944, the fate of the Western World hinged on whether the U.S. and its Allies could cross the English Channel, storm into France, and halt the German march across Europe.

France had already fallen to German troops and England was imperiled. The D-Day invasion was an attempt to turn back the German war machine.

Three weeks short of his 20thbirthday, Lampton was a Master Mechanic 2ndClass aboard LCF-31, a heavily armed landing craft that would be among the first vessels heading toward Omaha Beach.

“Our first duty was to stay out about 10 miles and protect from air attacks,” he said. “But there was no air attacks, so we were sent in the first wave … nobody seemed to be upset. We were just doing our jobs.”

The largest of the D-Day assault areas, Omaha Beach stretched more than six miles with the western third of the beach, which was backed by a seawall some 10 feet high. The entire beach was overlooked by cliffs 100 feet high. There were only five exits from the sandy beach — the best a paved road leading to a village.

The Germans, under Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, had built formidable defenses to protect this enclosed battlefield. The waters and beach were heavily mined, and there were 13 strong “resistance nests.” Numerous other fighting positions dotted the area, supported by an extensive trench system.

The defending forces consisted of three battalions of battle-tested veteran German troops, their weapons fixed to cover the beach with a hail of bullets and a swath of fire from the cliffs.

Omaha Beach was a killing zone.

From the beginning, everything went wrong at Omaha. Special tanks that were fitted with flotation devices sank in the choppy waters of the Channel. “They dropped 30 of those tanks in the water, and they all sunk,” said Lampton.

U.S. forces suffered more than 2,400 casualties. However, by day’s end approximately 156,000 Allied troops had successfully stormed Normandy’s beaches. Less than a week later, the beaches were fully secured, and more than 326,000 troops and 50,000 vehicles had landed at Normandy.

The D-Day invasion involved some 5,000 ships, carrying men and vehicles across the English Channel. It was an impressive armada. “As far as the eye could see, there were ships,” said Lampton. “We could see the shells from the battle wagons. It was like a streak of fire.”

Some 800 planes launched more than 13,000 paratroopers, many behind enemy lines. Another 300 planes bombed German positions along the beaches.

As a Master Mechanic 2ndClass, Lampton was in charge of a seven-man crew that tended two 12-cylinder diesel engines, which powered the craft, and two 6-cylinder diesels that provided auxiliary power. He was down in the engine room with two of his men when his life changed.

“We heard a report of ‘Shell bursts off the starboard bow,’” he said. “Then it was ‘Shell bursts off the port bow.’”

Then Lampton’s world went black.

“It was black as the ace of spades,” he said. “I was knocked out, and when I woke, I couldn’t see a thing. All power was out. I ran my tongue across my front teeth and thought, ‘My God, my teeth were knocked out. Turns out they were just a little chipped.”

Lampton never saw either of his engine room mates again. He didn’t know what happened, but he knew that water was rising in the engine room, and he had to get out. Groggy from a head injury and feeling his way through the dark, Lampton reached a ladder and climbed slowly, rung by rung until he reached an emergency hatch at the top.

“I wasn’t sure about opening the hatch,” he said. “It was the only time I got scared, I think. I thought for a minute we might be underwater, and if I opened the hatch …”

The very thought of opening that hatch and drowning caused him to lose sleep and suffer nightmares for years. Now we’d call it PTSD.

But Lampton jerked open the hatch and saw open sky above. He climbed out on to the deck, which was deserted. “There was no one there,” he said. “It was strange.”

The surviving crew of the LCF-31 had been picked up by a Coast Guard Cutter, CGC-16. Out of a crew of 72, only 18 survived. An excerpt from the cutter’s log describes its D-Day activities:

“0530, accompanied invasion barges into shore under severe shelling attacks and with mines going up all around us. 0730, LCF-31 hit by shell 800 yards off shore, sinking immediately. While engaged in picking up survivors, a shell struck PC-1261, which disintegrated, scattering men and debris over a wide area. While so engaged, shells and bullets were falling nearby, and just after last man picked up, small landing craft only few hundred yards off shore blew up. Proceeded to spot and picked up all living survivors.” (CGC-16 Log.)

In the fog of war, Lampton had been left in the damaged engine room aboard his landing craft. He knew the LCF-31 was sinking, and he had to get off. Wearing his “Mae West” life preserver, he went into the water — completely alone in the rolling sea as the D-Day invasion raged on Omaha Beach.

Lampton didn’t see the LCF-31 go under the waves. “She turned completely over, and I saw that black bottom,” he said. “Then the next time I looked, she wasn’t there.”

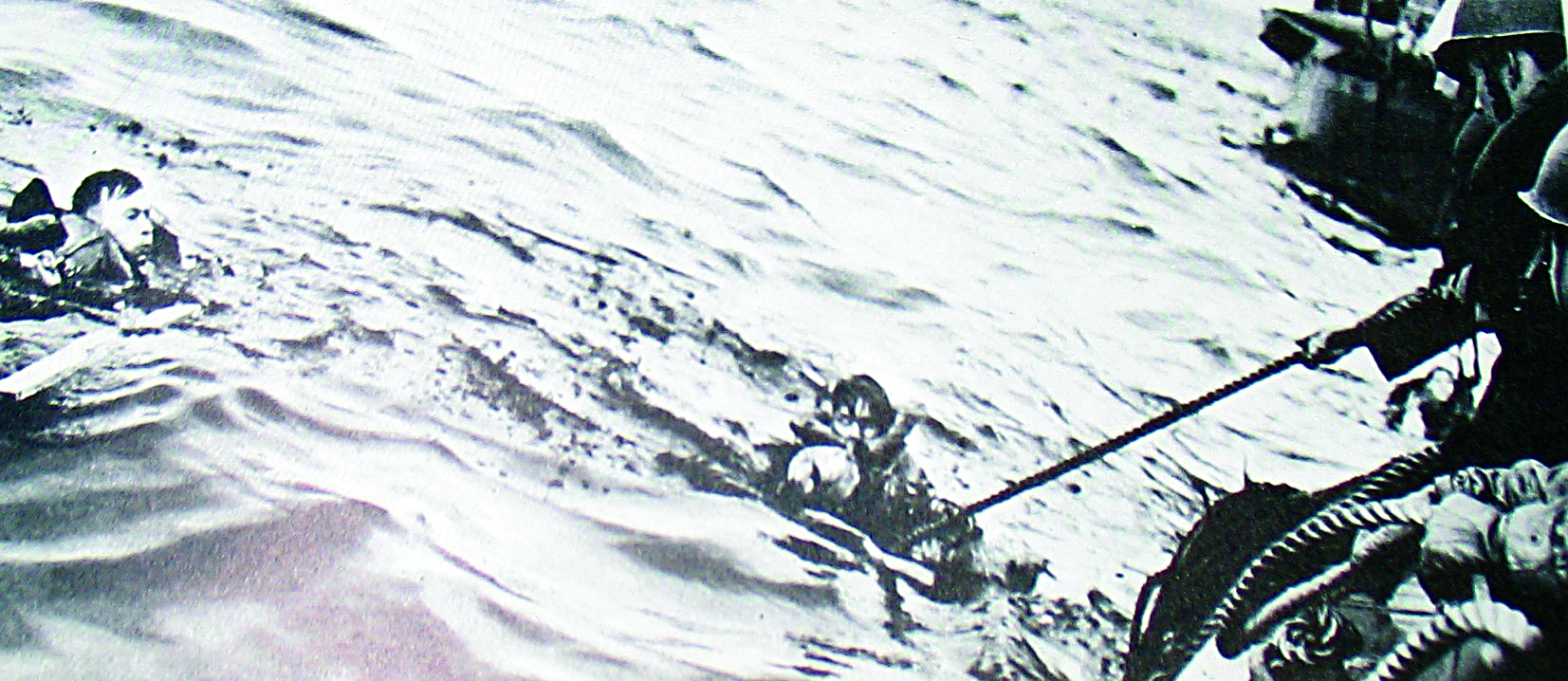

He remembers fading in and out of consciousness, kept alive thanks to the cumbersome but protective clothing he was required to wear. After a while he saw a soldier adrift, and the two paired up to await a rescue. After several hours, they were found by a U.S. Coast Guard Cutter, which was deployed to rescue sailors. (Lampton is pictured at his moment of rescue, holding rope, above.)

Lampton suffered that head injury and took shrapnel in his left leg. “My leg got infected and swelled up,” he said. “They thought they might have to cut my leg off, but I yelled like a son of a gun.”

Lampton was taken to a hospital ship and later transferred to a hospital in London. But when the Germans began the bombing the city, Lampton and others were evacuated to a hospital tent camp in central England. He was discharged from the Navy in 1946.

After the war, Lampton returned to civilian life and took a job working for the Chesapeake & Ohio railroad, working for 37 years before retiring. He met his wife, Elaine, aboard a train, and they were married in May 1947 and moved to Traverse City in 1973. During their 72 years together, they’ve raised two sons, and are still in love, though Elaine has been dealing with health issues recently.

A few years ago, Lampton took an Honor Flight, joining 63 other northern Michigan World War II veterans for a day-trip to Washington D. C. He was deeply impressed by Arlington National Cemetery and has made arrangements to be interred there, with Elaine, when the time comes.

On a wall in his “man cave,” Lampton has a display case of medals, including a Purple Heart, that pays tribute to his wartime experiences more than seven decades ago. Still, he asserts, he’s no hero.

“We were there, doing our job,” he stressed. “But we weren’t heroes.”

Below: Lampton in 1943 and today.

D-DAY BY THE NUMBERS

D-Day, also called “Operation Overlord,” is the name given to the landing of 160,000 Allied troops in Normandy, France, on June 6, 1944.

“D-Day” most likely comes from the army’s use of the term “undefined day,” or the first day of any operation.

American General Dwight D. Eisenhower commanded the invasion.

D-Day was originally scheduled for June 5, but the weather did not cooperate. The operation was pushed back to June 6, 1944.

There were five separate landings on 60 miles of the Normandy coast by American, British, and Canadian troops.

Code names for the five beaches where the Allies landed: Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword.

The D-Day invasion involved 5,000 ships carrying men and vehicles across the English Channel as well as 800 planes dropping over 13,000 men in parachutes. An additional 300 planes dropped bombs on German troops defending the beaches.

More than 100,000 Allied troops made it to shore that day.

The most difficult landing of D-Day was at Omaha Beach, where navigation issues lead to many men drowning before they even reached land. Omaha Beach also had the largest number of German troops. It is the Omaha Beach battle that is re-enacted in the opening of Private Ryan.

—Information courtesy of Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours

Trending

The Valleys and Hills of Doon Brae

Whether you’re a single-digit handicap or a duffer who doesn’t know a mashie from a niblick, there’s a n... Read More >>

The Garden Theater’s Green Energy Roof

In 2018, Garden Theater owners Rick and Jennie Schmitt and Blake and Marci Brooks looked into installing solar panels on t... Read More >>

Earth Day Up North

Happy Earth Day! If you want to celebrate our favorite planet, here are a few activities happening around the North. On Ap... Read More >>